Room Acoustic Design Elements

Thomas Wulfrank

When designing a space acoustically, a whole range of design elements is available to an architect and an acoustician. These elements are:

- acoustic reflector

- acoustic volume

- acoustically coupled volumes

- acoustic opening

- acoustic screen

- acoustic absorber

- acoustic diffusor

- acoustically transparent surface

This article describes first three elements: acoustic reflector, acoustic volume and acoustically coupled volumes.

Acoustic reflector

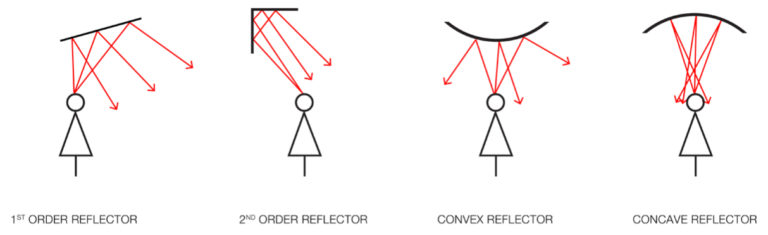

An acoustic reflector is any hard and smooth surface – or a combination thereof – that bounces incident sound like a mirror. Acoustic reflectors create specular acoustic refections. Acoustic reflectors can either be separate, free standing or free hanging elements (like a canopy above an orchestra), or they can be integrated into the architecture, for example as a part of walls or a ceiling. Acoustic reflectors can be of any size and shape, be it flat or curved (convex or concave), but this of course influences their acoustic behaviour. Reflective surfaces contribute to both early refections (the frst few bounces) and reverberation (after tens or hundreds of bounces).

Different types of acoustic reflectors.

Acoustic reflectors above the stage (symphony hall, Nouveau Siecle, Lille).

Acoustic reflectors above the stage (symphony hall, Nouveau Siecle, Lille).

Acoustic volume

Any enclosed volume consisting of multiple reflective surfaces – in other words any architectural space – will respond to sound with a physical process called reverberation. Reverberation is the result of sound bouncing consecutively, for tens or hundreds of times, off the reflective boundaries of the volume. Reverberation is heard by people in – or near – an acoustic volume as prolonging decay of a sound after the source of the sound has been switched off. The subjective criterion linked to reverberation is called reverberance. The size and shape of the acoustic volume, as well as the materials involved, govern how the reverberation is built up and also determine the quality of the reverberance: how long it lasts (temporal dimension), how loud it is (amplitude dimension), which timbre it has (frequency dimension) and where it comes from (spatial dimension).

Example of how reverberation builds up in an acoustic volume as multiple reflections bounce off the boundaries one after the other.

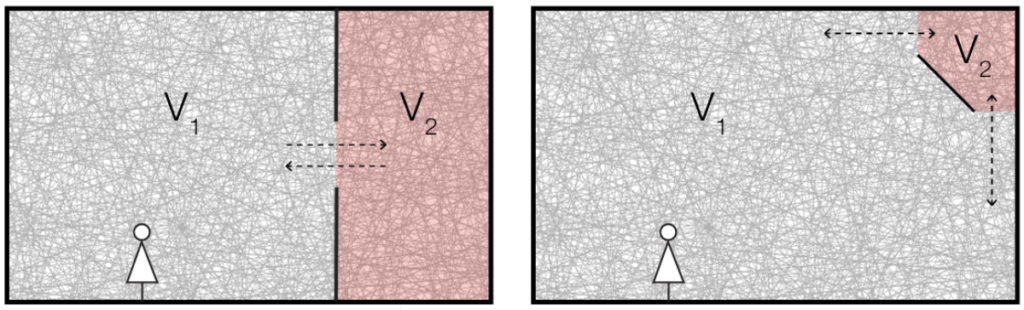

Acoustically coupled volumes

Two acoustic volumes can be connected (“coupled”) together through a sufficiently large opening. Acoustically, this has the effect that sound originating from the first volume (V1) will propagate from the first volume to the second volume (V2) through the opening(s) between the spaces and vice versa. In addition, under certain circumstances sound from the first volume having propagated to the second volume and having bounced around for a certain time will return to the first volume, opening up interesting acoustic possibilities.

Schematic principle of acoustically coupled volumes.

Schematic principle of acoustically coupled volumes.

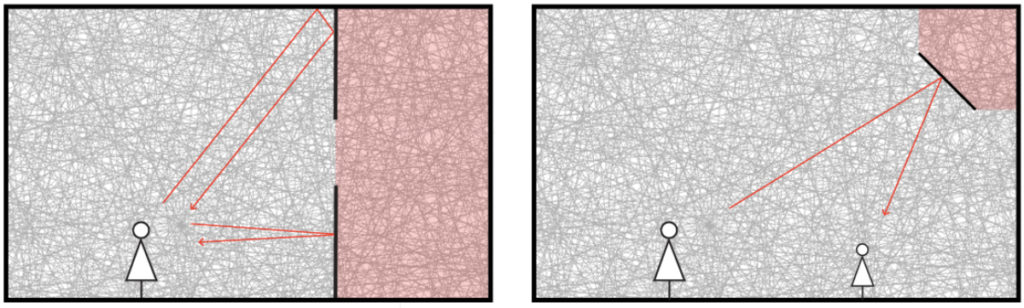

The (partial) surfaces between the two acoustic volumes can be used to create useful early lateral reflections in the first volume.

The (partial) surfaces between the two acoustic volumes can be used to create useful early lateral reflections in the first volume.

There are different types of acoustic coupling, depending on the size of the opening, the volumes of the coupled spaces and the amount of acoustic absorption materials inside each space. Firstly, when the coupling opening is small or when there is a lot of absorption inside the second volume, sound from the first volume will “disappear” into the opening to the second volume and will never come back. This is equivalent to having an acoustically absorbing opening. An example of this situation is the proscenium opening of a theatre auditorium, connecting the audience chamber to the stage house (flytower). Secondly, when the coupling opening is large or when there is little absorption in the second volume, both volumes will add up, creating a single large acoustic volume. An example of this are the side naves of churches, which are separated by colonnades from the central, main volume.

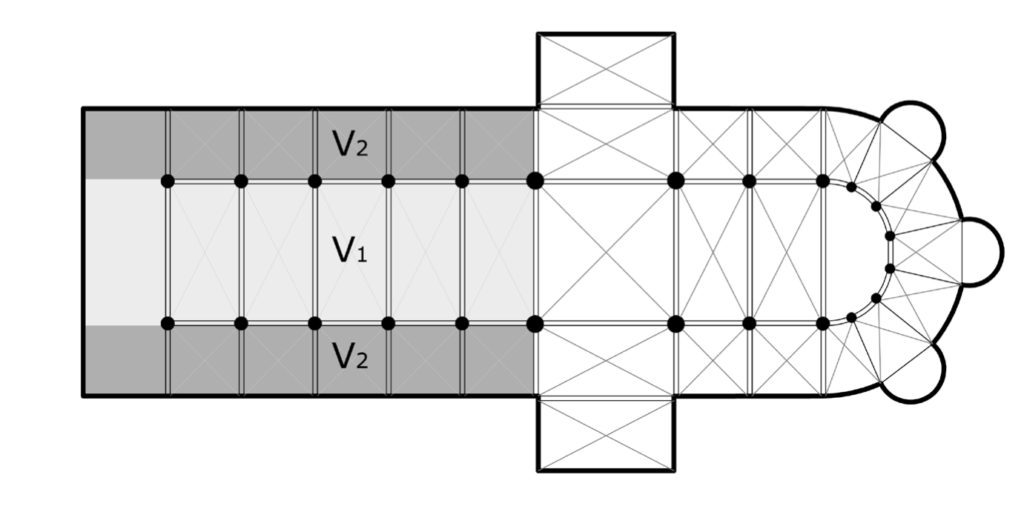

Example of a church, where the side naves (V2) are acoustically fully coupled to the central nave (V1), so that a single combined acoustic volume is obtained.

Example of a church, where the side naves (V2) are acoustically fully coupled to the central nave (V1), so that a single combined acoustic volume is obtained.

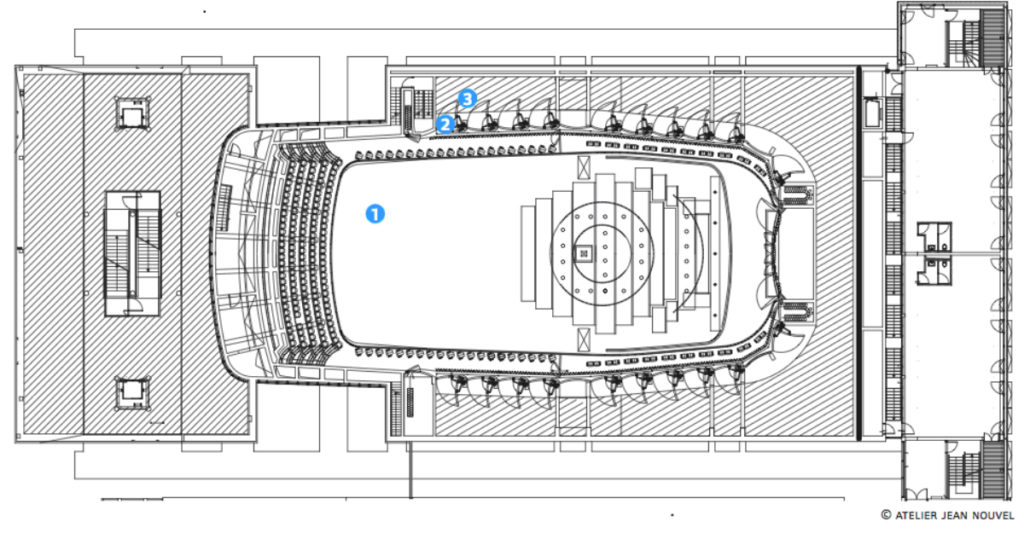

Finally, a special intermediate case is when the opening is small enough to obtain a long reverberation in the second volume, but at the same time big enough for this reverberation to return to the first volume. A typical example is a concert hall with reverberation chambers, such as the concert hall at KKL Luzern.

1. Main acoustic volume of the concert hall, 2. Doors of the reverberation chambers, 3. Reverberation chambers, which can be coupled to the main volume for richer reverberation.

1. Main acoustic volume of the concert hall, 2. Doors of the reverberation chambers, 3. Reverberation chambers, which can be coupled to the main volume for richer reverberation.

Example of reverberation chambers in the 1800 seat concert hall at KKL Luzern.

Example of reverberation chambers in the 1800 seat concert hall at KKL Luzern.

Acoustic coupling is a complex subject and should be studied with the help of a specialist acoustician.